Walking past a café near Victoria I heard a woman sitting outside it remark to her companion: “It’s strange, like there’s been this background music all this time and suddenly it’s not there.”

Well put. And those who’ve liked that music most were by this time turning up to help compose the British monarchy’s new tune, bustling out of the station towards Buckingham Palace, where early arrivals had already colonised the Queen Victoria Memorial, police officers were politely shooing people behind barriers because “the horses are coming”, and everyone had been made mildly damp by a moderate downpour. Brollies up. Chins up. The Queen is dead.

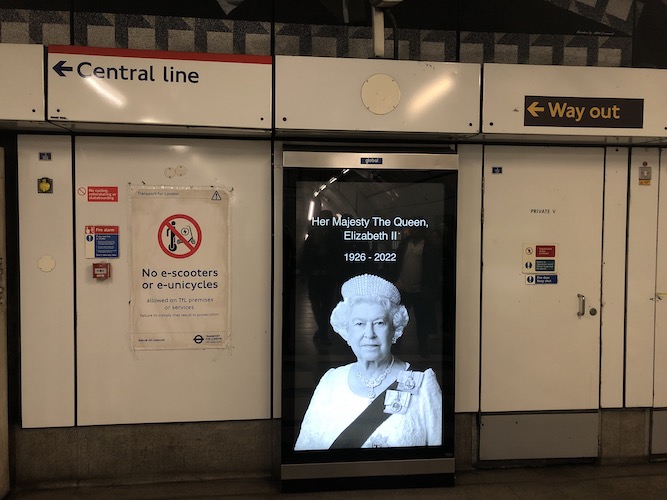

Yes, it was terribly British, right down to the many foreigners present, although earlier, elsewhere in central London, there had been few outward signs of that “nation united in grief” we’re hearing so much about. By 10am Network Rail had got their message out at Liverpool Street station, as had Transport for London at the entrance to the Underground and, poignantly, the Elizabeth Line.

On Charing Cross Road, the Outernet, another new feature of the capital had a large and impressive picture of the late monarch on display, and along Pall Mall a single black drape adorned a Reform Club balcony. When I walked past it again 15 minutes later there were two.

That was about it for my travels before noon. Still, the palace end of The Mall was filling up, and it was there that an association between the late Elizabeth and the nation’s capital could be felt. It is a link that formed part of the London of my small town childhood imagination, thanks mostly to television. Although now a Londoner for over 40 years, I still find it exciting to inhabit that construction of the mind for real. And what was London like when Elizabeth ascended to the throne in 1953, before I was even born? Old film footage from an unknown source returns us flickeringly to fragments of that post-war past.

But where else in London can traces of Elizabeth be found? In Parliament. In Westminster Abbey. At Wembley Stadium. In 2012 at the Olympic Park, later renamed after her. Yet the London buildings where she spent her childhood have been erased.

She was born on 21 April 1926 at 17 Bruton Street, a townhouse just off Berkeley Square in Mayfair, which belonged to her Scottish grandparents, the Earl and Countess of Strathmore. It and neighbouring houses were knocked down shortly before the war, and today’s 17 Bruton Street is an uncommunicative office building adjoining Berkeley Square House. A plaque marks the spot of the infant Elizabeth’s residence.

She later moved to 145 Piccadilly, a five-storey dwelling at the junction with Park Lane. In 1936 Elizabeth’s father became King George VI and the family moved into Buck House. It was just as well for them that they did because in 1940 the Piccadilly house was struck and badly damaged by German bombs. Today, the site is occupied by the InterContinental Hotel.

All of this gives a sense of the formal, ceremonial Elizabeth being very much of London, while at the same time traces of the early, more private one are intangible. Perhaps that is part of why Elizabeth II was so successfully enigmatic for so long, itself in integral aspect of her “soft power” and fascination for so many visitors to the capital.

No question, she put in a shift. And I’m quietly, mildly sad about her death: though I could do without the royalist grief performance and the wall-to-wall media output, the Queen has been part of the background music of my whole London life. Yes, it does feel strange that it has stopped.

From onlondon.com

Dave Hill: London traces of the late Elizabeth