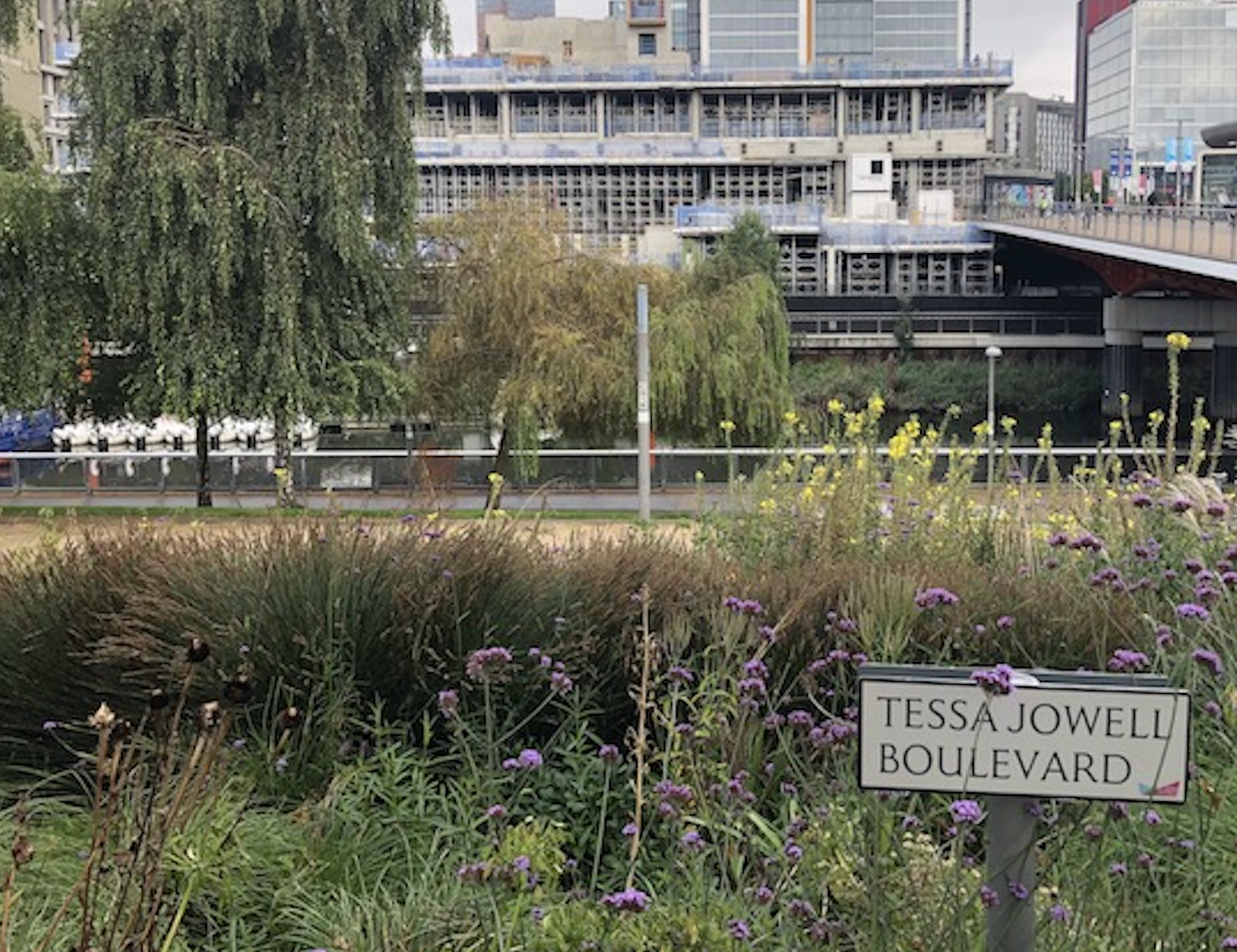

The best view is from Tessa Jowell Boulevard, the tree-lined walkway so named since 2019 in memory of the politician who made a huge contribution to London hosting the Olympic Games in 2012 and the creation of what is now called the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park.

On the other side of the Waterworks River, to the left of the London Aquatics Centre as you gaze, a quartet of buildings is taking shape that will be the homes of a new branch of the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), a second Sadler’s Wells dance theatre, a unified campus for the London College of Fashion (LCF) and the BBC’s successor to its former studios in Maida Vale.

The V&A and LCF structures have been “topped out”, the former earlier this month. Close by, a new campus for University College London (UCL) is at a more advanced stage. Occupying sites on both sides of the waterway south of the London Aquatics Centre, it is due to open its doors to students in September 2022.

This cluster of education and culture institutions is known collectively as East Bank and it has continued to emerge, albeit fitfully, throughout the pandemic. It is costing more money than it was meant to and is proving more tricky to construct than was hoped, yet it remains a beacon of potential, imagination and ambition in a London landscape darkened by Covid and Brexit uncertainties.

Why? Well, because there’s every reason to believe it is going to be great – an agglomeration of learning and creativity attractions such as the east of the capital has never seen. London’s Olympic proposition, as set before the International Olympic Committee in November 2004, placed great weight on hosting the Games being a catalyst for the physical, social and economic regeneration of the Lower Lea Valley far beyond the festival of sport. East Bank is that legacy promise taking shape.

The project also demonstrates, as did the delivery of the park as a whole in time for the Games, the value of national and London government working in productive partnership and of cross-party consensus, however scratchy. Initial credit for East Bank must go to Boris Johnson and George Osborne. Having secured a second term at City Hall and, after a fashion, installed himself, if largely nominally, in the chair of the London Legacy Development Corporation (LLDC) shortly after the Games, Johnson reached the conclusion that the park’s legacy as then planned lacked a key dimension.

After taking advice from others, he came up with the idea of a culture and education hub and dubbed it Olympicopolis – a typically Johnsonian reference to South Kensington’s Albertopolis which he hoped it would emulate. Osborne, Chancellor of the coalition government, provided £141 million for it. UCL, which is meeting its own costs, was already on board at that stage.

By the time Sadiq Khan became Mayor in May 2016 most of the ingredients were in place, though several have changed: the Borisese title was expunged with almost comical speed; two enormous residential blocks planned to rise beside the complex and help finance it were replaced with four shorter ones following an arcane kerfuffle over the view of St Paul’s from a mound in Richmond; The Smithsonian, which Johnson had eagerly wooed got cold feet; the BBC’s involvement was confirmed

The East Bank name went public with revised plans in June 2018 and ground was broken in July 2019. Work stopped for a while when the pandemic hit – Mayor’s orders – and the budget has grown through a combination of compensation for delays, uncertainty over supplies of labour and materials and technical difficulties. But, in marked contrast to its conspicuous discrimination against London in so many other areas, Johnson’s national government has helped out the LLDC with the extra costs Covid has brought about.

The scheme’s finances are still challenging, as they say, but the investment will surely pay dividends for decades, if not centuries. The East Bank partners have been making efforts to engage and involve local communities – to break down barriers to participation that still extend to making use of the park more generally. There is a psychology at work which dissuades some Londoners from feeling that the park belongs to them.

There are hopes that the effects of the pandemic have done something to change that, with the park staying open as a free space for relaxation and recreation. East Bank can play its part in building on that and in so doing form a connecting thread between the regeneration ambitions of the Games project, the success of the Games themselves and the ideal of an open, expansive and effervescent London that subsequent events can seem to have consigned to the past.

from onlondon.com

Dave Hill: Olympic Park East Bank can lift London gloom in 2022