Last week, Conservative-run Royal Borough of Kensington & Chelsea (RBKC) decided to re-think how best to accommodate bicycle travel on and around Kensington High Street. In December, temporary segregated lanes that had been introduced down both sides of the road a few weeks earlier were taken out. The council does not intend to put them back. Its latest move was greeted with anger by campaigners: for them, the Kensington High Street scheme was already a cause célèbre.

Denunciations raced up through the gears. The London Cycling Campaign called RBKC’s decision “a devastating development” and asked Sadiq Khan and Transport Secretary Grant Shapps to intervene. Chris Boardman, policy adviser to British Cycling, said in a video that the decision “puts lives at risk” and brought “no demonstrable benefit to anyone”. Soliciting media coverage, he declared it “a national story”. The Mayor’s cycling and walking commissioner Will Norman called the decision “shameful” and vowed “we’re not giving up”.

The fury focussed on this shop-lined stretch of the A315 in inner west London distills a cluster of related and often hotly-contested issues about surface transport priorities, the management of road space, air quality, neighbourhood environments and about where the power to determine how London’s streets are organised should rightly rest. The story of the Kensington High Street cycle lanes is a parable of London road rage. It can teach us many things.

*****

Whose idea were the lanes in the first place? They were RBKC’s idea: part of its response to national government guidance about post-first lockdown travel published in July. This followed the government’s push, announced in May, to encourage more travel by bicycle (and by foot) to help facilitate social distancing.

Keep that fact in mind when weighing the rights and wrongs of this affair. Note too that Kensington High Street is RBKC’s road, not the government’s. It isn’t Sadiq Khan’s and Transport for London’s either. As things stand, RBKC has every right to do what it likes about road space on Kensington High Street. That’s why it and no one else took the decision to put the bike lanes there.

The push to assign more road space for exclusive cycling use reflected the enthusiasms of Prime Minister Boris Johnson and his erstwhile media supporter and now transport adviser Andrew Gilligan. Money to pay for this and other “active travel” measures was included in the first government bailout of TfL.

Although at odds with Gilligan and Shapps over the government’s general attitude to TfL’s Covid-induced financial crisis, the Mayor was aligned with it on nurturing more cycling. Hence, Khan and TfL’s Streetspace programme, also announced in May 2020, complete with its own guidance for boroughs and the heroic claim that it “could increase cycling ten fold post-lockdown.”

That was the context in which RBKC brought cycle lanes to Kensington High Street. Their status was temporary and the expectation at the time was that they would be in place for up to 18 months – the maximum time allowed under the experimental traffic orders that have enabled bike lanes and other Streetspace measures, such as Low Traffic Neighbourhoods, to be installed without prior public consultation. The lanes came into full operation on 15 October.

*****

What was the impact of the lanes? This is, of course, disputed. RBKC decided on 2 December to remove them following what the council officer report to last week’s leadership team meeting described as “strong representation from local residents, businesses and road-users”.

There had been complaints about increased congestion due to less road space being available for motorised vehicles and that congestion resulting in more tailpipe pollution; complaints about loss of badly-needed Christmas run-up trade at a time when lockdown measures had been eased; complaints about problems being created for disabled people. The lanes were gone by the middle of the month.

Adverse reaction was intense from pro-bike lane politicians, campaign groups – which included the local Better Streets for Kensington & Chelsea – and the considerable array of cycling enthusiasts who work for large media organisations. The Daily Mail, which is as fervently anti-cycle lanes as other media are in favour, reported that Gilligan phoned the council to “beg” RBKC to leave the lanes in place and “pledged” that Johnson himself would cycle down one for a photo opportunity.

Some of the language and imagery deployed were emotive: the lanes, which were created by erecting rows of easily-removable bollards or “wands” – they were temporary, after all – were repeatedly described as being “ripped out“. Photographs of children cycling along the lanes were liberally deployed on websites and social media platforms. Extinction Rebellion conducted a raid.

But the council’s critics also claimed that “hard facts” supported their view that the lanes were necessary and popular. “Removal of the cycle lanes does seem to be more of a knee-jerk reaction to calls for them to be scrapped than anything backed up by data,” one cycling journal observed.

In early November Will Norman said “new data from TfL” showed that cycling on Kensington High Street had “more than doubled to over 3,000 a day“. In December, Green Party London Assembly candidate Zack Polanski said the number of cyclists using the street “has doubled to over 4,000 a day“. But those figures aren’t the only ones around.

*****

What do “the data” reveal? Assertions about “the data” are a frequent feature of arguments about the provision and efficacy of cycling infrastructure. The parable of the Kensington High Street bicycle lanes teaches us to beware the definite article. Sometimes there are different sets of data that don’t necessarily point to the same conclusions and which it might anyway be difficult to draw firm conclusions from. In the case of Kensington High Street, “the data” seem capable of telling a number of different stories rather than a single, definitive one, or at least of being understood that way.

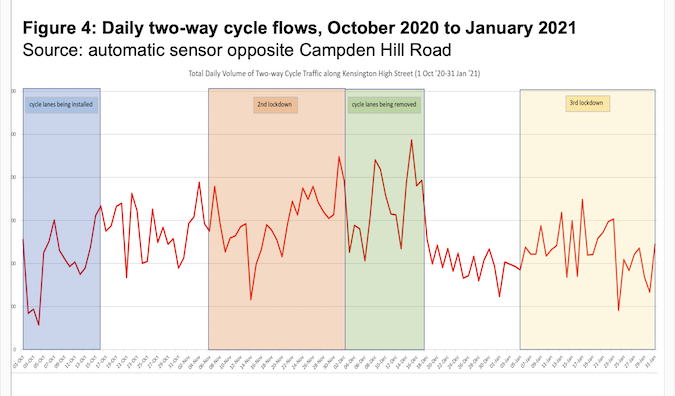

An automatic sensor was set up to record the number of bikes that passed in both directions each day. As the graph from the report (reproduced below) shows the numbers captured by the sensor have fluctuated considerably from day to day throughout the four months beginning at the start of October.

For parts of November, daily totals recorded exceeded 3,000 and even briefly 4,000 near the end. In other parts of November they were lower, included a brief dip to just above 1,000. The average daily figures for the full four months were as follows: October 2,384 a day; November 2,897; December 2,825; and January, the first full month without the lanes, 2,235.

What do these figures indicate? The RBKC report notes that average daily cycle flows were 50 per cent higher in the second half of October after the lanes were opened than in the first half, when the lanes were under construction. It also notes that numbers fell by 50 per cent in the second half of December, after the lanes had been fully removed, compared with the first half.

This looks thoroughly consistent with the view that the existence of the lanes led to increased cycling. Indeed, for some of the monitoring period, up until late November, a fault with the sensor resulted in what the RBKC report some “inconsistent” undercounting, especially of bikes heading east (though how much undercounting isn’t specified). The numbers also show an increase compared with manual one-hour counts of bicycles made by TfL in October 2018.

However, the RBKC report also says that “well before the pandemic struck the High Street was seeing over 2,000 cycle trips a day”. It notes that figures for weekends had become higher in relation to weekdays, suggesting a substantial rise in leisure cycling – a feature of pandemic cycling figures London-wide – when the main purpose was to encourage an alternative to daily public transport and car use. It also notes that the single busiest day for bikes throughout the whole four months was 15 December, when the lanes had all but gone.

Other questions come to mind. How many of those who used the lanes were cyclists already and making use of a new facility and how many were new cyclists? How many of any new ones would have stuck with it? What effect did the Christmas period have on the figures? What about the weather?

There’s masses more material in the RBKC officer report – too much to deal with here – including analyses of motor vehicle displacement and pollution. You might not like the council’s decision to take out the cycle lanes, but immersion in the detail of the report at least provides an insight into why its leaders felt justified in concluding that “the data” is inconclusive about the lanes’ effects.

*****

What about road safety? Earlier this month, in an obvious attempt to put pressure on RBKC, City Hall released the findings of a survey of local residents. The main finding was that 56 per cent of residents of RBKC support a protected cycle lane on Kensington High Street compared with 30 per cent who don’t.

What this proves is debatable. With so much publicity about cyclists’ safety and activists’ insistence that lanes save lives, was the balance ever likely to be the other way round? In a talk delivered in September 2019, former TfL surface transport director Leon Daniels noted the gap often revealed between what people say about cycle lanes in general and how they feel when someone wants to put one on a street they often use. The survey also found that support for those on Kensington High Street was lower among people who lived nearer to it, though TfL didn’t highlight that.

Publication of the survey was accompanied by a press release which said “collision data” show that Kensington High Street is “one of the borough’s worst casualty hotspots for cycling, with 15 people killed or seriously injured while walking or cycling over the past three years.”

How many were killed? How many of those killed or seriously injured were cyclists? TfL has clarified that, in fact, no cyclists or pedestrians were killed on Kensington High Street during the period in question. They were also able specify that of the 15 collision victims seriously injured, nine were cyclists.

The RBKC officer report quotes “approved data” from TfL for the previous three years (2016-2018), showing there were eight cycling casualties whose injuries were classified as “serious” during that three-year period and no deaths.

The Mayor’s press release also said the 15 cyclists or pedestrians mentioned – of whom nine were cyclists, as we now know – “represents the highest casualty rate for people cycling of all main roads in the borough and is significantly above the Greater London average.”

What defines a main road in this context? TfL explains that it is one “controlled by RBKC that is also part of the Strategic Road Network”. Kensington High Street is one such road. The only others in RBKC are Holland Park Avenue and Notting Hill Gate. These are actually continuations of each other with different names (and the scene of a previous bicycle lane battle between TfL and the Mayor and RBKC).

How is a “casualty rate” for individual roads calculated? TfL has helpfully informed On London that the ones referred to were arrived at using government road safety statistics for the three year period ending January 2019. These are figures for injuries of all degrees of seriousness sustained in road collisions recorded by the police using Department for Transport guidance.

Overall casualty rates are worked out per kilometre of road. TfL says the rate for Kensington High Street was 24 collisions per kilometre, for Notting Hill Gate 23 per kilometre and for Holland Park Avenue, 9.5. (The lower figure for the latter might in part be a reflection of the nature of the street, which has far fewer shops on it and therefore fewer motor vehicles parking and pulling out into the road).

What is “the Greater London average?” This turns out to be a measure of something different, defined by TfL as the percentage of all collisions on a street involving people riding bicycles. TfL says the Greater London average for this is 20 per cent while that that of Kensington High Street is 32 per cent. So a higher proportion of road collisions on that street involves cyclists than across Greater London as a whole.

One lesson of this parable is that road safety statistics can confuse…

*****

What will happen next? What should? RBKC’s leaders have opted to “not install temporary cycle lanes, but develop plans to commission research into transport patterns in the post-Covid world, in partnership with local residents and local institutions including academic partners”. This is the rather wordy proposition which, following the speed with which the temporary lanes were abandoned, has infuriated their ecumenical array of critics.

RBKC, though, offers a stout defence. The officer report documents progress towards the council’s target of having 70 per cent of the borough’s residents living within 400 metres of a cycle route of some kind – a programme funded by TfL. It says 68 per cent was reached last year and the figure would have risen to 74 per cent had TfL funded two local cycleways the council had approved pre-Covid. By contrast, says the report, the Kensington High Street lanes, if kept in place, would have increase the percentage to only just under 72 per cent.

Johnny Thalassites, RBKC’s lead member for environment planning and place, who took the decisions to put the lanes in and to take them out again, says “residents had complained that they couldn’t get to their houses and disability groups told me they felt in danger when being dropped off by cabs. Emergency services told me the lanes were delaying their crews. Businesses told me their customers were staying away due to traffic jams and they feared losing footfall in the run up to Christmas.”

He wants a more nuanced approach to street design in the area, one which weighs a range of different factors: “Cycling infrastructure matters when half a million more people cycle in London compared to the 1990s. It also matters that 26,000 people a day take the bus down our High Street.”

TfL’s Director of Investment Delivery Planning, Alexandra Batey, sent the council a long letter on 5 February telling them why they’d done the wrong thing, but a fortnight earlier the High Court had ruled that the Streetspace guidance to boroughs was illegal (TfL has appealed). There have been murmurs about TfL taking control of Kensington High Street, but that might be a bit hopeful.

Such changes need government sanction. After Westminster Council rejected the Mayor’s plans for getting Oxford Street pedestrianised, one of his senior advisers intimated privately that asking a hostile Tory government to hand that famous road over to TfL would probably be a lengthy waste of time. Would Grant Shapps look kindly on a request from a Labour Mayor he doesn’t like to annex a prime avenue of Tory Kensington?

So RBKC isn’t budging. Its defences look quite strong. After all, the cycle lanes were only temporary. Kensington High Street is RBKC’s road. The administration does have a mandate from the borough’s voters. And, as the parable might conclude, that’s democracy.

Image captured from this video.

From onlondon.com

Dave Hill: The parable of the Kensington High Street bicycle lanes